Two weeks after my ninth birthday, something was very wrong. My body was shedding pounds on my already skinny frame, I was urinating constantly, and I was perpetually thirsty. Eventually, things got so bad that I lost consciousness and when I woke up, I was in a pediatric ICU, IV’s flowing out of each arm. A young doctor walked into the room and sat at my bedside. She took my hand in hers and said, “you have something called type 1 diabetes.”

A Life-Altering Experience

My life was forever changed; I would need to regulate my blood glucose by pricking my finger numerous times a day and injecting insulin. Too much insulin and I could become dangerously hypoglycemic, leading to death. But if my blood glucose remained elevated for long periods of time, complications could occur like loss of sensation in my fingers and toes, heart attacks, strokes, kidney disease, and even blindness. Type 1 diabetes is the last thing you think about before going to bed and the first thing on your mind when you wake up in the morning. But, it did something else for me – it showed me my calling.

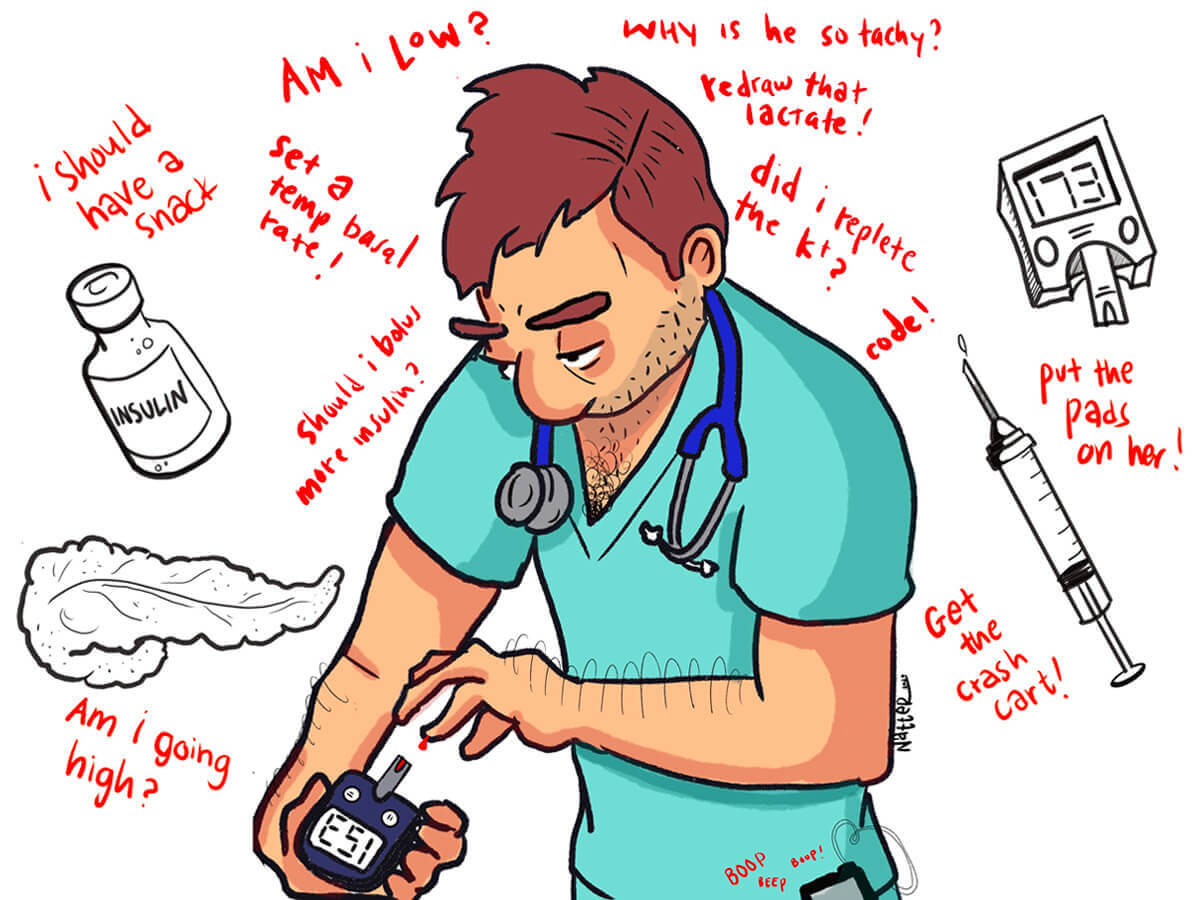

Managing Type 1 Diabetes in Medical School

Many who live with chronic illnesses that go into medicine have some trepidation initially. I was no exception. What I found helpful was being upfront and candid from the get-go. In medical school, I made sure my advisors and professors were aware that I was Type 1 and would potentially need to test my blood sugar or adjust my insulin pump in class so that they knew I was not cheating or being distracted by my phone. My medical school was extremely supportive and on board with me checking my blood sugar or drinking some juice if my blood sugar went low during an exam. Other programs may differ and may have separate protocols, which one can work out if they ask upfront.

Things were more difficult during clinical rotations, but again, I would let my senior residents and attendings know what I may need to do in order to control my blood glucose and all of them were supportive and understanding. I was most fearful during my surgical rotation when one can spend uncountable hours retracting large swaths of fat, fascia, and muscle in the OR, oftentimes bypassing lunch.

As a type 1 diabetic, the idea of having a hypoglycemic episode in that environment kept me up at night. What ended up happening though was something that stuck with me. My senior resident pulled me aside the first day after I told him about my fears. He said, “surgeons are human too. You need to do whatever you need in order to keep yourself healthy. If you gotta scrub out, then scrub out, and everyone will understand.” It also makes sense since a medical student passing out on to the sterile field is a bad look for everyone. On a more granular note, I always keep snacks and glucose tablets on me in the hospital. In my bag I keep backups of all my medications because one never truly knows when the day will end.

My Calling

Now, as a senior internal medicine resident, I am that doctor who sits at the bedside and delivers difficult news. Being one of many doctors who are also patients gives me the insight to know what it’s like to deal with chronic illness. This is not something that is easy to teach in medical school. The empathy I provide to my patients after delivering a life-altering diagnosis is so important. Remembering my own experience has given me the unique ability to empathize and understand my patients on a deeper level. I am responsible for not only giving my patients the information and treatment they need, but also the emotional support they need to handle their newfound situation.

Being both a doctor and patient allows me to not only be a better medical practitioner, but also a better patient advocate. When a patient receives difficult news, many may feel too overwhelmed to collect their thoughts in order to ask questions. As someone who has been in their shoes, I can try to anticipate their questions and make sure they go home with better peace of mind.

My diagnosis is something I would wish on no one. However, it has given me a great gift: my calling and a deep connection to my patients.